We thought the best way to recoed Andy's biography was to include a series of interviews over the years. |

|---|

BIOGRAPHY

Spencer Leigh Interview

SL: I told Andy that the last time I met him was just after he joined Pink Floyd!

AR: Joined - I wish! I was playing with Roy Harper who is very pally with Dave Gilmour. Dave came to see a show that we did in London at the Dominion Theatre at the end of 1980 and it just co-incided with the time that Snowy White joined Thin Lizzy. He'd been playing the Wall with Floyd and had done all the initial shows. Luckily for me he wasn't available for some extra dates that they'd added to the end of the Wall tour, well it wasn't a tour really, they played Los Angeles, New York and London. That was it, that was all they expected to do - those 3 places. Then they got an offer they couldn't refuse, to go and play in Germany, or do Europe basically, where they set up in Germany and all of Europe came to them. And they needed a guitarist, Dave had seen me play and I was using a lots of effects pedals and stuff like that and he knew I was a reasonable bloke and so he phoned me up and offered me the job. I was very reluctant, it took me about 2 seconds before I agreed.

SL: Were the gigs of a size that you'd never played before?

AR: Yes, I've never done anything like that before. It was actually terribly interesting because, it is that classic stadium rock. It was an eye opener, I loved doing it and it was encouraging in many ways. They treated me very nicely, they paid me lots of money and they treated me like an adult, none of which you quite knew what to expect. I mean I thought I might just be a side man and they'd be cracking the whip saying " is that a beer you're drinking - I think not". They just respect you and let you get on with it. But the expectation is that you are going to deliver.

SL: Are you more worried that when you go out on stage that the sound may not be right?

AR: No, they do a lot of sound checking. They would sound check for two or three hours, but I mean to be honest you are so far away from the audience, there are 25,000 people a night there, or thereabouts, but the first the first row of the audience are sixty or seventy feet away its an awful long way away. You don't really see them, once you are under the lights you don't see anything except when they do that thing with the cigarette lighters. So actually you are quite inured from the whole thing. The backstage is hundreds of yards away from anywhere that the punters can get close to you. Which I found a bit odd!

The other thing is that the show is about alienation, and barriers between performers and their audience so a physical barrier was built during the first half of the show. And at the end of the first half there was a solid white wall the full width of the stage, with the band behind it, invisible to the crowd. The second half some of it took place in front of the wall but it wasn't till the very end of the show that the barrier is physically taken down. It was theatre and that was what I liked about it all. I spent a lot of my life in theatre and through that television and film and it just suited me. I enjoyed the technical side of it and how it was put together. It was brilliant!

But it was definitely odd being that far away from the crowd and in fact I finished playing in Earls Court and the next night I was back playing in the Hank Wangford Band at the Pegasus in Stoke Newington where the front row of the audience is two feet away and was just so relieved to see sweating people right in front of me, you know. Rather than have this ocean of empty blackness in front of me.

SL: Is it great fun playing with Hank Wangford?

AR: Yes, I got involved with Hank at the end of the seventies. For the three years I did it, it was absolutely my ideal gig, because it combined comedy, theatre and music and it was the best of all those things for me really. I loved the role playing, I loved going on stage as somebody other than myself. I always had a problem going on stage as myself really. That was why the brief time I was a solo artist, I never really felt comfortable with it and to go and be Brad Breath and not Andy Roberts was a great joy.

SL: I've always thought when I've seen the Hank Wangford Band, and I love them, I just wish he was a better vocalist.

AR: Sam is what he is, he invented a wonderful person in Hank. He espouses terrific values. He's a semi-pro, and remains a semi-pro. The reality is that he suffers from terrible Bronchitis and he just doesn't have the power in his lungs. And that's just a physical thing, he's a fabulous writer and he's a great human being - he does an awful lot of good work in Romania. He's a very interesting character.

SL: You've been scoring films of late and in particular one which was set in Liverpool, a film called Priest. A very csontroversial film written by Jimmy McGovern. How did you get involved with that?

AR: It was directed by a lady called Antonia Bird, whom I've know for quite a long time. When I made a conscious decision that I didn't want to be a solo artist I was at the same time being asked to write music for theatre and I took that opportunity and that worked out quite well and got me into television.

This was in the seventies, the middle seventies, and I ended up through a series of chance circumstances as musical director of the Royal Court Theatre, Sloane Square in London. And while I was doing the work at the Royal Court, with Max Stafford-Clark who'd just taken over from Stewart Birge, there was a young Assistant Director there called Antonia Bird and that's how we met. We did some work together and it was good work. Culminating in a tour we did 1983. It was the first time I worked with Paul McGann in fact. It was a Trevor Griffiths play called 'Oi for England'. A single act play that we toured round youth clubs in London and then brought into the Royal Court Theatre for a month. It was a very hard hitting play about skinheads and racism and Paul played the lead in that and Antonia directed.

It really forged a relationship and then when she went to the BBC as a trainee I did a lot of things with her at the BBC and did a drama series called 'Thin Air' which was very successful and the 'The Men's Room' which was a serial about middle class sex basically which went very well because it had a lot joyful nudity and she had developed 'Priest'. Originally Jimmy had written it as a television four parter and it got changed over time to a single drama on film and Antonia was always in there to direct it. And at that point it was natural for her to ask me to do the music, particularly because of the Liverpool connection.

SL: And did you have to choose other peoples music as well?

AR: No there was very little of that. It did have the Dusty Springfield version of 'Anyone who had a heart'. Jimmy was quite specific about music in the script, sometimes and particularly with hymns, as a, he'll probably hate me for calling him a lapsed catholic, I don't think he is, I think in his heart he's still very catholic. He'd specified hymns in the screen play and I had to a lot of serious research into masses and the music that goes with catholic services. But I think that it might have been written that it was playing in the background. He does have a very strong sense of music, but if it wasn't, it was something we'd decided was playing in the classroom when the girl has an epileptic fit which was brought upon by being abused. The Dusty Springfield version came about because we tried the get the Cilla one but couldn't clear it for love nor money. But Dusty had just put out a greatest hits album and it's a lovely version.

SL: Presumably you get a video of the film and say this bit requires 15 seconds of music and then you decide what you want to write?

AR: Yes, it works that way, I had to be around while the film was being shot a lot because there was a lot of specific live action. I mean, when you've got a church full of people singing a hymn, somebody has actually got to be there making sure that what you end up with is something can be workably cut together at the end of it. So the hymn has to be sung a lot of times, somebody has got to be playing the organ and you have to make sure that the people who are singing it are in time with the organ, so just out of shot is me jumping up and down conducting the congregation.

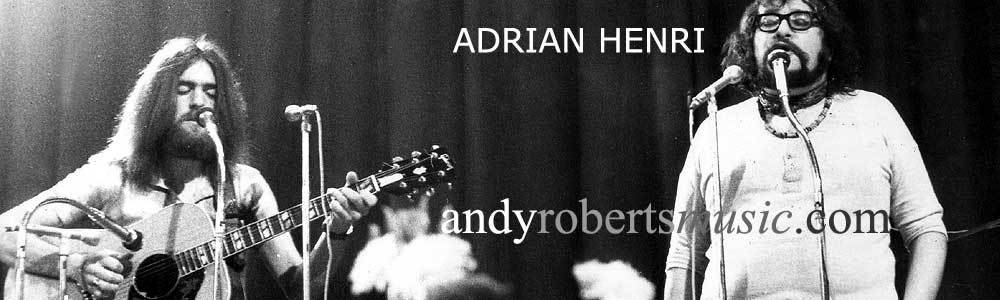

SL: You are best known in Liverpool for playing music to the poems of Adrian Henri and Roger McGough. In all those instances you were doing it, were the poems actually written first?

AR: I think so. I think latterly maybe Adrian might have, once Liverpool Scene was up and running, he might have been writing things thinking this is something the band would do. But there was never any sense that the poem was written to suit the music.

SL: Did you find that they both wrote quite musically?

AR: Adrian does. Adrian really is a musician and when he reads, performs his poetry, it's just like a musician riffing, you know. If he had been a sax player he would have been a good one.

SL: I always think that when he closes his eyes and moves around.

AR: Yes, he is. He really feels it. Roger is not the same thing at all. He speaks very fast and is very precise and has a very quick delivery. And it bothers him slightly, because the music demands that he slows down a little bit. After he has relaxed and actually slows down he confesses how much he enjoys it. But it's very different with the two of them.

SL: And in fact you don't actually leave bands , because they can always come back again?

Andy laughs

SL: Plainsong is back now and promoting a new album, 'New Place Now'. What made you decide to be back in Plainsong?

AR: It was re-meeting Iain 18 years after he'd moved to America. I was sitting on the smoking ruins of my second marriage and visiting a girl friend down in Brighton and looking for something to do in the evening. I got the Brighton Argus, which is the local paper, and there was an advertisement in there for a chap called Iain Matthews playing at a pub in Brighton. I said to Sally, I used to work with a bloke called Iain Matthews, it can't possibly be the same one, for a start he lives in America and he would never play a pub in Brighton, I mean, it just isn't his style at all. And she said, well lets go anyway and you can always tell him that you've seen someone with the same name. We went, and it was Iain, working as a duo with a guy called Mark Hallman, so that was a terrific encounter. Not having seen him for a good number of years. So they were playing in London in a couple of days after that and he said come down and do a couple. So I went down and we did a couple of old Plainsong songs on the show. It went wonderfully well. So the next year he came back to do a solo tour and asked me to do it with him with just the two of us. For a couple of years we worked as a duo, just off and on, I mean all the time I was doing the tele and films which is really what I do now. Again the notion was, well if we could recruit a couple more members we could be back to the Plainsong concept. Plainsong was always something we believed in. So that was when we got Griff and Julian (Dawson), originally, and then Julian dropped out, Clive (Gregson) joined us. -

SL: You choose the four voices do you, so it's very carefully structured?

AR: No, you try and find people who can write, and people who lean towards the type of material that we lean to. I mean, it's a generational thing. Clive is younger than us. Iain, Griff and I are all the 'baby boomers', lived through the fifties and grew up with fifties rock and roll and through the sixties we were all professional players by 67/68. So we naturally lean towards things that are American, the post war generation did, because of the chewing gum and nylons approach. So I think that colours it.

SL: Lets take a song from the Plainsong album that I know you are involved with 'Valley got a new dog'?

AR: Right - it was a good few years ago. It probably wouldn't have existed as a song if I hadn't run the germ of it past Clive when we were getting the album together. I went to Austria to visit some friends in a place called Mayrhofn, which is a ski resort. I've got some friend who run a hotel out there. And they asked me to do a show. I don't do shows, I really don't go out and do solos, its always a wrench to go and do that. There was a guy called John Fiddler, who was the lead singer in a Medicine Head and he came out to do the show. I was pretty, kind of myself, I don't think it was a bad show, but it wasn't particularly hot on the rock and roll flashy stuff. Whereas John was good at the flashy stuff, he's the sort of guy who changes into the jeans with the ripped knees to go on stage. It's not my style at all. I remember at the time feeling that he'd stolen the affection of my pals. They all kind of thought that he was bloody brilliant and that I was kind of OK, but he'd been fantastic. And that was it, an Austrian valley that had got a new dog. I told Clive the story and we wrote the song around that.

Interviewed by Spencer Leigh on 5th March 1999 at St. Helens, The Citadel, prior to Plainsong concert, and recorded for BBC Radio Merseyside.