We thought the best way to recoed Andy's biography was to include a series of interviews over the years. |

|---|

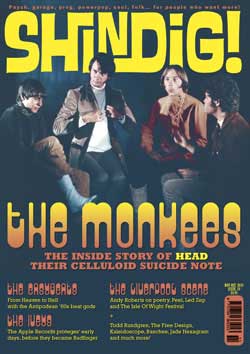

SHINDIG: A lot has been writt

en about the material you recorded with Bob Sargeant that resulted in the album, Everyone. Confusion reigns supreme over that one, down to the title – is that the name of the album or the name of the band! Somehow it came across like two separate mini-albums – your half and his half. How do you feel about the record today?

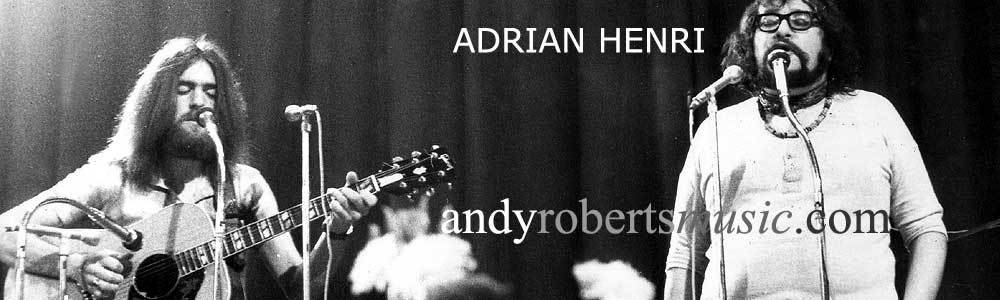

AR: The background to the formation of Everyone is worth exploring, as an indication of my state of mind at that time. Liverpool Scene broke up messily at a gig at the London School of Economics in May 1970. The band split between Mike Evans and Percy Jones on one side, and Adrian Henri and myself on the other.

It was clear to me that my time in Liverpool was also at an end, so I returned up north to clear out my room at 64 Canning Street and I headed to London, to stay with my parents, at first. On my way south I went first to Leeds to spend a night with a gorgeous girlfriend there, and then on to the Kettering area to drop in on Principal Edwards Magic Theatre. They were old friends from the touring circuit, and at that time they were renting a large property called something like Broughton Grange Farm, and living as a commune. I went drinking with Les their lights guy that lunchtime, and returned to the farm half-cut, and started messing around with a motor bike they had there. I totally lost it on some gravel, went down to my left and ripped my left arm open to the bone, at the elbow. I was cleaned up and stitched at the hospital, heavily strapped and bandaged. The next day my Mum came up to take me back to London, where I remained unable to play for 7 weeks.

During that time, Sandy Roberton arranged for an advance from RCA, for me as a solo artist. A regular visitor to my parents’ place that summer was Paul Scard; Paul (with Andy Rochford) had been Liverpool Scene’s roadie for the last few months of the band’s existence, and they were as keen as I was to continue our working relationship in the future. Bouncing ideas off Paul, I decided that I didn’t want to be a solo artist, but that I wanted to form a band to be called Everyone, to reflect the lack of a leader. Later on this was referred to as Andy Roberts with Everyone or sometimes Andy Roberts’s Everyone, but that was never my intention. I just wanted to be in a band, and I thought the name was a good one.

I began writing songs for the first album. The first 2 were Ivy (Climbing Up A Castle Wall) and Don’t Go Down To The Ministry. These were both in the set when, at the end of July, Adrian Henri and I put together a band (which appeared under the name Liverpool Scene) for 3 dates in Norway. This was an old booking we couldn’t wriggle out of. We opened at the Sonia Henie Museum in Oslo, followed by 2 highly successful gigs at the Molde Jazz Festival. These were my first dates since the motor bike crash, and the band was myself, David Richards on bass, John Pearson on drums, with Alan Peters on trumpet and guitar. In a strange way this was a try out for Everyone, and it went very well indeed.

Now, I had never led a band since I was at school in the early 60s: my university band, The Trip, already existed before I joined, and was a co-operative. So I had no experience at all. At first I had talked with people I knew around where my parents lived – Guy Price (bass with The Temeraires) and Nig King (drummer with The Blackjacks) both turned me down. Sandy Roberton had suggested David Richards from a band he already managed which was splitting – Paul Kent’s band P.C. Kent. Dave and I really hit it off in Norway, musically and personally. I had also by then approached John Pearson and John Porter. They were both acquaintances from touring days, and I rather idealistically thought that if the band were good friends then we’d play better musically. I quickly learned the error of that little theory!

I decided I wanted a 5-piece, with a keyboard player. John Porter suggested Bob Sergeant, whose band Junco Partner was folding in Newcastle, and I offered Bob the gig on the basis of hearing their album. I had never met him at all, until we started rehearsing seriously in early August, in a rented house close to Stonehenge! Bob was a lovely bloke, a strong singer and writer with great experience, but we never found common ground musically until there were a few glimmers of understanding right at the end.

Our first gig was on 28th August 1970, playing to 250,000 people on the warm-up day of the 3rd Isle of Wight Festival. I have a review which says,

SHINDIG: “The day’s line up included two survivors from the 1969 event, the ever-present Gary Farr and “Everyone” – basically the Liverpool Scene without Adrian Henri – both of whom gave a good account of themselves.”

AR: Well, not so good that they could tell the difference, apparently! Our London debut was at the Marquee, for which I lost my voice completely, so it was a disaster. We tried again at the Speakeasy, where someone spiked me, so I was away with the fairies. It all seemed doomed. The recording was difficult between Bob and me. I even gave him the vocal on my song Ivy in the hope that it would improve things, but it didn’t work and the song was shelved for ever. Before it even came out I knew it was all over the place, and I hated it. My first move was to change personnel. We lost John Porter (because I thought 2 guitars were cluttering the sound), but that made little substantive difference. It was tough, apart from the strengthening of my bond with David Richards.

One night in November 1970 we played at Southampton University. Andy Rochford had copped off with a girl, and decided to stay down in Southampton. Paul Scard was fine with that, and he alone drove us back to London. I ended up at John Pearson’s flat in Bruton Place, with Paul as well, drinking tea, smoking dope, the usual. It was maybe 2am when Andy Rochford phoned, asking Paul to go back to Southampton to pick him and the girl up, as their place to stay had fallen through. Paul, bless him, didn’t hesitate to do as his mate requested. It was a cold night. Paul picked them up, and on the way back, in Basingstoke, a flatbed lorry hit a patch of ice, jackknifed going round a roundabout just ahead of them, and the trailer came scything round into our van. Andy and his girl were asleep, lying down on the seats; they were badly cut about, but Paul was upright, driving, and the trailer decapitated him. He was 19 years old.

The first I heard about it was the following morning, at my parents’ house, when anxious friends of my Mum and Dad called up. It was in the Stop Press column in the Daily Telegraph (remember those?) that I had been killed. In all the wreckage they had found my guitar case with Liverpool Scene stenciled on it, and had assumed I was the victim.

I have had to blank the aftermath, at least where Paul is concerned. I remember his funeral, and the financial chaos of losing the van and all our gear, but Sandy picked up the pieces for us. We hadn’t even finished the album before he died. I fulfilled all the outstanding dates I could, as an acoustic trio with Dave Richards on bass and John Pearson on congas and tablas. Once the gigs were over I went into a deep hole, as you can imagine. I have probably only ever seen Bob, or John Porter, a couple of times since then. The last time I saw Bob was at the launch, at the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios, of Ken Garner’s In Session Tonight – the definitive book on the John Peel sessions. That was in 1993.

SHINDIG: An alternate version of the album includes your take on Neil Young’s ‘Cowgirl In The Sand.’ How did you come to choose that cover and did you have any problems securing the rights to record it?

AR: Here’s how it works, Jeff. When he/she writes a song, the writer has the right of first usage; no-one can record it before the writer does, without his/her express permission. Once it is recorded, however, anyone can record it without any further need for permission from the author, as it is deemed to be in the public domain. All you must do, of course, is to pay the appropriate royalty due on the amount sold. So for instance anyone can record any Beatles song they wish to!

Cowgirl In The Sand was a favourite late night jam for us during the Everyone rehearsals, and one day we recorded it at Sandy’s suggestion. It was not a track I would have wanted out in the UK, but after the demise of the band it was put on an album in Holland. It was already pressed before anyone told me.

SHINDIG: Urban Cowboy seemed to take a long time to release, featuring recordings over a three year period from 1971-73. Was it difficult coming up with material for that album or were you just overwhelmed with outside activities?

AR: Definitely the latter! Nina And The Dream Tree had been released in September 1971 to great acclaim. I had toured the US with Iain Matthews and Richard Thompson that summer, and I returned for a solo tour to promote the Dream Tree album all through that autumn, supporting Steeleye Span (the new line-up with Martin Carthy). At the end of that tour, in December 1971, I had formulated the basis of Plainsong with Iain, and the whole of 1972 was taken up exclusively with that band, so I didn’t return to solo recording until early 1973. 2 of the tracks on Urban Cowboy are by Plainsong – the title song and All Around My Grandmother’s Floor.

SHINDIG: Lots of old friends on this one, from Richard Thompson and Iain Matthews to Neil Innes and Martin Carthy and a return to writing with Mike Evans from hyour Liverpool Scene days. Do you look back with fondness on this one today?

AR: I can see that it is pretty disjointed because of the 18 months between the first and last tracks, but it has some pretty strong material, and over all I was very happy with it, and I think it still has merit. The friends make it even more special. By the way, Grandmother’s Floor was written during the Liverpool Scene’s time together – according to Ken Garner a version was in our session for John Peel’s show Top Gear on 19th January 1969. That’s about 4½ years before Urban Cowboy was released!

SHINDIG: Finally, The Great Stampede. Perhaps one of your strongest bands, featuring Gerry Conway and Pat Donaldson from Fotheringay, and some great contributions from Zoot Money and Ollie Halsall. How did you get along with Ollie? Was he as awe-inspiring as his legend makes him out or was he just as excitied to be working with you?

AR: By August 1973 I had learned how to pick a band! These were all my greatest friends from my time as a session player, and I had the deepest respect for each and every one of them. Zoot Money is a genius. It was a fantastic experience to record that album – I loved it all, and it was the absolute best I could achieve at that time. The only wild card was Mick Kaminski. This was long before his time with the Electric Light Orchestra. Mick was playing with a band called Joe Soap, and Sandy had used him on other sessions and recommended him to me. I remember saying we’d use him on day one, and see how it went. He fitted right in, and it was a magic week recording the basic tracks.

Ollie, I knew from Liverpool days. He had been the drummer with a band called The Music Students. Then the guitarist left the band and Ollie took over – within 6 months he was the best player on Merseyside. Probably the most awesomely talented guitarist I have ever met. I saw him with Patto from time to time in the late 60s. At the time of The Great Stampede he was still with his wife and children, living in Abbots Langley, not far from my first proper house in Bushey, and I would drop over from time to time. We had played together earlier in 1973 on Neil Innes’s first solo album, How Sweet To Be An Idiot. I’d say we were friends. But he only played on one track, Speedwell; all the other guitar playing is mine! We overdubbed Ollie at the old Livingston Studio in Barnet, after the basic tracks were finished at Olympic.

SHINDIG: The reissue is now out with five bonus tracks. Can you tell us about them?

AR: These were outtakes and curios I had in my personal collection. I would have left the reissued CD exactly as the vinyl had been, but I was overruled. So to add value the 5 extra tracks were added. The full details are in the booklet with the CD, and I can’t add to them, really.

So here they are (slightly edited):

Home at Last. Written during the year of Plainsong, but never, I think, performed by them. This was from a bunch of songs recorded with Neil Innes on piano and Hammond organ, and David Richards on bass, during the GRIMMS time in early 1973. Viv Stanshall and Neil had been friends of mine increasingly since I played with Bonzo Dog Freaks in 1970-1. David was my stalwart right hand man from 1970 onwards, into Plainsong and beyond. To not use him for the Great Stampede was a huge conscious decision, but we resumed for another 2 years with GRIMMS, and he remains a pal to this day. Originally this song was called Same Tune, Three Times. Makes sense to me.

Lost Highway. Iain Matthews was largely responsible for introducing me to ‘classic’ country music – the kind I like. I was powerfully moved by the life and legend of Hank Williams, and I still am. Dead at age 29, alone, on the slide, full of booze and drugs in the back of a Cadillac on the way to a gig. Here, I’m trying on Hank’s voice, flat-toned, no vibrato. Not one of his own songs, but a great one nonetheless.

Living In The Hills Zion. I had never heard of Marcus Garvey or Rastafarians before I went to Jamaica on honeymoon in May 1973. Went to see The Harder They Come. Saw that wonderful moment when the artist Ras Daniel Heartman rises from the ocean and shakes his locks. I have a sketch of his on the wall to this day. Anyway, we were told that, as a rule, true rastas liked to live apart from other people, in the hills of the interior, but there was a group who were approachable, living at a place called Cascade, above the beach at Negril. Negril today is a nightmare of hotels, but then it was a 7-mile long strand of white sand with no buildings at all, and deserted. Utterly enchanting. Jacqui and I hired a car, and drove there, dodging land crabs all the way. Found a sign to Cascade and started driving up, and up, and up. Eventually the stones blew a tyre, so we got out and walked. We found Booli at his house. There followed a magic day when we smoked herb, ate, swam, talked and shared. They took me to see their ganja fields deeper in the hills - acres of redtops, 8 feet tall. Lovely gentle spiritual people, far from society, self-sufficient, their only tools a ratchet knife and a machete. I looked Cascade up on the internet a few days ago. Now, it’s a golf course. The track has another outing on the rumba bass, and is a demo. I never recorded the song again.

New Karenski. In the late summer of 1971 I toured the US in an acoustic trio with Iain Matthews and Richard Thompson. Iain was the star – he was newly signed to Mercury Records, so Richard and I roomed together all across America. This was before Richard became a Muslim, and calmed down. In Boston, at a club called the Poison Apple, I met Karen Goskowski. At that time I thought she could be the one. There was a slight problem – she was married, but living apart from her feller. Later on they sorted it out, and such is life. But my songs Poison Apple Lady, Urban Cowboy, and this one are about her. She worked for an airline, so could come to places as we played them, but she never made it to England. Sandy Koufax’s Tropicana, a motel on La Cienaga Boulevard in LA, was a favourite place to stay, ‘cause it was down the street from Doug Weston’s Troubadour club, where we played twice. The swimming pool had cracked in an earthquake and leaked all its water away. I think it was $12 a night. The air-conditioning didn’t work. It was there Richard and I met Don Everly, and Mo from the 3 Stooges. Later on it was Tom Waits’s home for a while. You get the picture.

Having a Party. Zoot Money on Hammond, David Richards on bass, and John Halsey on drums. I first met ‘Admiral’ Halsey when he was playing in a talent contest at the Rhodes Hall in Bishops Stortford. I was there supporting a friend’s band from school. John’s band, Felder’s Orioles, won first prize. My lot came third. Later on he played with Ollie Halsall in Timebox, and Patto. Later still he was in GRIMMS, and the Rutles. He now manages the best pub in Cambridge. This is a reggae version of the Sam Cooke classic, the way I’d like to have done it at Dickie Wong’s club on the Red Hills Road. Zoot’s voice on the fadeout is sublime.

SHINDIG: How would you rate this amongst all your other releases?

Great Stampede? The best by far, but in an admittedly small field!

AR: When I began to write for theatre in late 1973 I found something I liked more than making records, so I stopped trying to be a star. Good move – the records never made me a penny, the musicals still earn money today, not much, but still it’s real money.

Eventually I wrote film scores for 17 years – those films are shown every year throughout the world, mostly on TV in out of the way places. I think I was better at scoring than I was at making records; I loved the whole process, and I was never more full of confidence than during my time in Hollywood.

about the material you recorded with Bob Sargeant that resulted in the album, Everyone. Confusion reigns supreme over that one, down to the title – is that the name of the album or the name of the band! Somehow it came across like two separate mini-albums – your half and his half. How do you feel about the record today?

AR: The background to the formation of Everyone is worth exploring, as an indication of my state of mind at that time. Liverpool Scene broke up messily at a gig at the London School of Economics in May 1970. The band split between Mike Evans and Percy Jones on one side, and Adrian Henri and myself on the other.

It was clear to me that my time in Liverpool was also at an end, so I returned up north to clear out my room at 64 Canning Street and I headed to London, to stay with my parents, at first. On my way south I went first to Leeds to spend a night with a gorgeous girlfriend there, and then on to the Kettering area to drop in on Principal Edwards Magic Theatre. They were old friends from the touring circuit, and at that time they were renting a large property called something like Broughton Grange Farm, and living as a commune. I went drinking with Les their lights guy that lunchtime, and returned to the farm half-cut, and started messing around with a motor bike they had there. I totally lost it on some gravel, went down to my left and ripped my left arm open to the bone, at the elbow. I was cleaned up and stitched at the hospital, heavily strapped and bandaged. The next day my Mum came up to take me back to London, where I remained unable to play for 7 weeks.

During that time, Sandy Roberton arranged for an advance from RCA, for me as a solo artist. A regular visitor to my parents’ place that summer was Paul Scard; Paul (with Andy Rochford) had been Liverpool Scene’s roadie for the last few months of the band’s existence, and they were as keen as I was to continue our working relationship in the future. Bouncing ideas off Paul, I decided that I didn’t want to be a solo artist, but that I wanted to form a band to be called Everyone, to reflect the lack of a leader. Later on this was referred to as Andy Roberts with Everyone or sometimes Andy Roberts’s Everyone, but that was never my intention. I just wanted to be in a band, and I thought the name was a good one.

I began writing songs for the first album. The first 2 were Ivy (Climbing Up A Castle Wall) and Don’t Go Down To The Ministry. These were both in the set when, at the end of July, Adrian Henri and I put together a band (which appeared under the name Liverpool Scene) for 3 dates in Norway. This was an old booking we couldn’t wriggle out of. We opened at the Sonia Henie Museum in Oslo, followed by 2 highly successful gigs at the Molde Jazz Festival. These were my first dates since the motor bike crash, and the band was myself, David Richards on bass, John Pearson on drums, with Alan Peters on trumpet and guitar. In a strange way this was a try out for Everyone, and it went very well indeed.

Now, I had never led a band since I was at school in the early 60s: my university band, The Trip, already existed before I joined, and was a co-operative. So I had no experience at all. At first I had talked with people I knew around where my parents lived – Guy Price (bass with The Temeraires) and Nig King (drummer with The Blackjacks) both turned me down. Sandy Roberton had suggested David Richards from a band he already managed which was splitting – Paul Kent’s band P.C. Kent. Dave and I really hit it off in Norway, musically and personally. I had also by then approached John Pearson and John Porter. They were both acquaintances from touring days, and I rather idealistically thought that if the band were good friends then we’d play better musically. I quickly learned the error of that little theory!

I decided I wanted a 5-piece, with a keyboard player. John Porter suggested Bob Sergeant, whose band Junco Partner was folding in Newcastle, and I offered Bob the gig on the basis of hearing their album. I had never met him at all, until we started rehearsing seriously in early August, in a rented house close to Stonehenge! Bob was a lovely bloke, a strong singer and writer with great experience, but we never found common ground musically until there were a few glimmers of understanding right at the end.

Our first gig was on 28th August 1970, playing to 250,000 people on the warm-up day of the 3rd Isle of Wight Festival. I have a review which says,

SHINDIG: “The day’s line up included two survivors from the 1969 event, the ever-present Gary Farr and “Everyone” – basically the Liverpool Scene without Adrian Henri – both of whom gave a good account of themselves.”

AR: Well, not so good that they could tell the difference, apparently! Our London debut was at the Marquee, for which I lost my voice completely, so it was a disaster. We tried again at the Speakeasy, where someone spiked me, so I was away with the fairies. It all seemed doomed. The recording was difficult between Bob and me. I even gave him the vocal on my song Ivy in the hope that it would improve things, but it didn’t work and the song was shelved for ever. Before it even came out I knew it was all over the place, and I hated it. My first move was to change personnel. We lost John Porter (because I thought 2 guitars were cluttering the sound), but that made little substantive difference. It was tough, apart from the strengthening of my bond with David Richards.

One night in November 1970 we played at Southampton University. Andy Rochford had copped off with a girl, and decided to stay down in Southampton. Paul Scard was fine with that, and he alone drove us back to London. I ended up at John Pearson’s flat in Bruton Place, with Paul as well, drinking tea, smoking dope, the usual. It was maybe 2am when Andy Rochford phoned, asking Paul to go back to Southampton to pick him and the girl up, as their place to stay had fallen through. Paul, bless him, didn’t hesitate to do as his mate requested. It was a cold night. Paul picked them up, and on the way back, in Basingstoke, a flatbed lorry hit a patch of ice, jackknifed going round a roundabout just ahead of them, and the trailer came scything round into our van. Andy and his girl were asleep, lying down on the seats; they were badly cut about, but Paul was upright, driving, and the trailer decapitated him. He was 19 years old.

The first I heard about it was the following morning, at my parents’ house, when anxious friends of my Mum and Dad called up. It was in the Stop Press column in the Daily Telegraph (remember those?) that I had been killed. In all the wreckage they had found my guitar case with Liverpool Scene stenciled on it, and had assumed I was the victim.

I have had to blank the aftermath, at least where Paul is concerned. I remember his funeral, and the financial chaos of losing the van and all our gear, but Sandy picked up the pieces for us. We hadn’t even finished the album before he died. I fulfilled all the outstanding dates I could, as an acoustic trio with Dave Richards on bass and John Pearson on congas and tablas. Once the gigs were over I went into a deep hole, as you can imagine. I have probably only ever seen Bob, or John Porter, a couple of times since then. The last time I saw Bob was at the launch, at the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios, of Ken Garner’s In Session Tonight – the definitive book on the John Peel sessions. That was in 1993.

SHINDIG: An alternate version of the album includes your take on Neil Young’s ‘Cowgirl In The Sand.’ How did you come to choose that cover and did you have any problems securing the rights to record it?

AR: Here’s how it works, Jeff. When he/she writes a song, the writer has the right of first usage; no-one can record it before the writer does, without his/her express permission. Once it is recorded, however, anyone can record it without any further need for permission from the author, as it is deemed to be in the public domain. All you must do, of course, is to pay the appropriate royalty due on the amount sold. So for instance anyone can record any Beatles song they wish to!

Cowgirl In The Sand was a favourite late night jam for us during the Everyone rehearsals, and one day we recorded it at Sandy’s suggestion. It was not a track I would have wanted out in the UK, but after the demise of the band it was put on an album in Holland. It was already pressed before anyone told me.

SHINDIG: Urban Cowboy seemed to take a long time to release, featuring recordings over a three year period from 1971-73. Was it difficult coming up with material for that album or were you just overwhelmed with outside activities?

AR: Definitely the latter! Nina And The Dream Tree had been released in September 1971 to great acclaim. I had toured the US with Iain Matthews and Richard Thompson that summer, and I returned for a solo tour to promote the Dream Tree album all through that autumn, supporting Steeleye Span (the new line-up with Martin Carthy). At the end of that tour, in December 1971, I had formulated the basis of Plainsong with Iain, and the whole of 1972 was taken up exclusively with that band, so I didn’t return to solo recording until early 1973. 2 of the tracks on Urban Cowboy are by Plainsong – the title song and All Around My Grandmother’s Floor.

SHINDIG: Lots of old friends on this one, from Richard Thompson and Iain Matthews to Neil Innes and Martin Carthy and a return to writing with Mike Evans from hyour Liverpool Scene days. Do you look back with fondness on this one today?

AR: I can see that it is pretty disjointed because of the 18 months between the first and last tracks, but it has some pretty strong material, and over all I was very happy with it, and I think it still has merit. The friends make it even more special. By the way, Grandmother’s Floor was written during the Liverpool Scene’s time together – according to Ken Garner a version was in our session for John Peel’s show Top Gear on 19th January 1969. That’s about 4½ years before Urban Cowboy was released!

SHINDIG: Finally, The Great Stampede. Perhaps one of your strongest bands, featuring Gerry Conway and Pat Donaldson from Fotheringay, and some great contributions from Zoot Money and Ollie Halsall. How did you get along with Ollie? Was he as awe-inspiring as his legend makes him out or was he just as excitied to be working with you?

AR: By August 1973 I had learned how to pick a band! These were all my greatest friends from my time as a session player, and I had the deepest respect for each and every one of them. Zoot Money is a genius. It was a fantastic experience to record that album – I loved it all, and it was the absolute best I could achieve at that time. The only wild card was Mick Kaminski. This was long before his time with the Electric Light Orchestra. Mick was playing with a band called Joe Soap, and Sandy had used him on other sessions and recommended him to me. I remember saying we’d use him on day one, and see how it went. He fitted right in, and it was a magic week recording the basic tracks.

Ollie, I knew from Liverpool days. He had been the drummer with a band called The Music Students. Then the guitarist left the band and Ollie took over – within 6 months he was the best player on Merseyside. Probably the most awesomely talented guitarist I have ever met. I saw him with Patto from time to time in the late 60s. At the time of The Great Stampede he was still with his wife and children, living in Abbots Langley, not far from my first proper house in Bushey, and I would drop over from time to time. We had played together earlier in 1973 on Neil Innes’s first solo album, How Sweet To Be An Idiot. I’d say we were friends. But he only played on one track, Speedwell; all the other guitar playing is mine! We overdubbed Ollie at the old Livingston Studio in Barnet, after the basic tracks were finished at Olympic.

SHINDIG: The reissue is now out with five bonus tracks. Can you tell us about them?

AR: These were outtakes and curios I had in my personal collection. I would have left the reissued CD exactly as the vinyl had been, but I was overruled. So to add value the 5 extra tracks were added. The full details are in the booklet with the CD, and I can’t add to them, really.

So here they are (slightly edited):

Home at Last. Written during the year of Plainsong, but never, I think, performed by them. This was from a bunch of songs recorded with Neil Innes on piano and Hammond organ, and David Richards on bass, during the GRIMMS time in early 1973. Viv Stanshall and Neil had been friends of mine increasingly since I played with Bonzo Dog Freaks in 1970-1. David was my stalwart right hand man from 1970 onwards, into Plainsong and beyond. To not use him for the Great Stampede was a huge conscious decision, but we resumed for another 2 years with GRIMMS, and he remains a pal to this day. Originally this song was called Same Tune, Three Times. Makes sense to me.

Lost Highway. Iain Matthews was largely responsible for introducing me to ‘classic’ country music – the kind I like. I was powerfully moved by the life and legend of Hank Williams, and I still am. Dead at age 29, alone, on the slide, full of booze and drugs in the back of a Cadillac on the way to a gig. Here, I’m trying on Hank’s voice, flat-toned, no vibrato. Not one of his own songs, but a great one nonetheless.

Living In The Hills Zion. I had never heard of Marcus Garvey or Rastafarians before I went to Jamaica on honeymoon in May 1973. Went to see The Harder They Come. Saw that wonderful moment when the artist Ras Daniel Heartman rises from the ocean and shakes his locks. I have a sketch of his on the wall to this day. Anyway, we were told that, as a rule, true rastas liked to live apart from other people, in the hills of the interior, but there was a group who were approachable, living at a place called Cascade, above the beach at Negril. Negril today is a nightmare of hotels, but then it was a 7-mile long strand of white sand with no buildings at all, and deserted. Utterly enchanting. Jacqui and I hired a car, and drove there, dodging land crabs all the way. Found a sign to Cascade and started driving up, and up, and up. Eventually the stones blew a tyre, so we got out and walked. We found Booli at his house. There followed a magic day when we smoked herb, ate, swam, talked and shared. They took me to see their ganja fields deeper in the hills - acres of redtops, 8 feet tall. Lovely gentle spiritual people, far from society, self-sufficient, their only tools a ratchet knife and a machete. I looked Cascade up on the internet a few days ago. Now, it’s a golf course. The track has another outing on the rumba bass, and is a demo. I never recorded the song again.

New Karenski. In the late summer of 1971 I toured the US in an acoustic trio with Iain Matthews and Richard Thompson. Iain was the star – he was newly signed to Mercury Records, so Richard and I roomed together all across America. This was before Richard became a Muslim, and calmed down. In Boston, at a club called the Poison Apple, I met Karen Goskowski. At that time I thought she could be the one. There was a slight problem – she was married, but living apart from her feller. Later on they sorted it out, and such is life. But my songs Poison Apple Lady, Urban Cowboy, and this one are about her. She worked for an airline, so could come to places as we played them, but she never made it to England. Sandy Koufax’s Tropicana, a motel on La Cienaga Boulevard in LA, was a favourite place to stay, ‘cause it was down the street from Doug Weston’s Troubadour club, where we played twice. The swimming pool had cracked in an earthquake and leaked all its water away. I think it was $12 a night. The air-conditioning didn’t work. It was there Richard and I met Don Everly, and Mo from the 3 Stooges. Later on it was Tom Waits’s home for a while. You get the picture.

Having a Party. Zoot Money on Hammond, David Richards on bass, and John Halsey on drums. I first met ‘Admiral’ Halsey when he was playing in a talent contest at the Rhodes Hall in Bishops Stortford. I was there supporting a friend’s band from school. John’s band, Felder’s Orioles, won first prize. My lot came third. Later on he played with Ollie Halsall in Timebox, and Patto. Later still he was in GRIMMS, and the Rutles. He now manages the best pub in Cambridge. This is a reggae version of the Sam Cooke classic, the way I’d like to have done it at Dickie Wong’s club on the Red Hills Road. Zoot’s voice on the fadeout is sublime.

SHINDIG: How would you rate this amongst all your other releases?

Great Stampede? The best by far, but in an admittedly small field!

AR: When I began to write for theatre in late 1973 I found something I liked more than making records, so I stopped trying to be a star. Good move – the records never made me a penny, the musicals still earn money today, not much, but still it’s real money.

Eventually I wrote film scores for 17 years – those films are shown every year throughout the world, mostly on TV in out of the way places. I think I was better at scoring than I was at making records; I loved the whole process, and I was never more full of confidence than during my time in Hollywood.

BIOGRAPHY

So Who’s This Andy Roberts Then…?

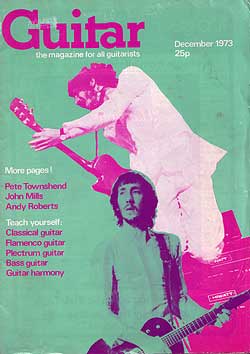

Sometime in the ‘80s I bought an LP called Home Grown, by one Andy Roberts, at a jumble sale. I knew nothing about the man but it had a really atmospheric, slightly creepy cover – of a man and a dog, at least one of whom had a hang-dog expression – and music inside some of which, most especially the lengthy ’Applecross’, only added to the intrigue and mystery. It was, I later discovered, only one of three different versions of the LP (this one the RCA pressing), and only one of several albums the man had released under his own name during a very short period in the early ‘70s – having previously been a member of the equally (to my generation) obscure Liverpool Scene – after which he seemed to disappear from view.

There was only one CD, an early ‘90s compilation, which was tantalising in the eclectic brilliance of its contents and yet still – in providing only one brief quote to the writer of the notes on that compilation – the perpetrator of this music seemed to remain fascinatingly elusive.

But I like musical underdogs, I like mysteries and I sometimes like a challenge. In 2004 I suggested to John Reed at Sanctuary that I had a hunch his label now owned an amount of Andy Roberts recordings and would they like me to look at a new compilation. It turned out that they did and they would. I also noticed that Roberts himself now had a website ( www.andyrobertsmusic.com ) and decided to get in touch. Luckily, while Andy was, and remains, very critical – overly so, in my view – about the quality of his own work, he was also prepared to accept the validity of a new 2CD anthology and engage in a process of selecting tracks – including, in several cases, comparing/contrasting several different mixes and versions of tracks from both the Sanctuary archive and his own collection of reel-to-reel demos and suchlike.

The whole process of selecting the tracks was actually a lot of fun, and Andy was a joy to work with. Often the bringing together of vintage artist, label-hired compiler and a label who owns much or all of the work and has no legal obligation to let the artist have any say over its repackaging can be fraught with tension, but not in this case – well, possibly between Andy and Sanctuary (as it was very much up to them to hammer out the deal for licensing the half dozen previously unreleased tracks and photos from Andy), but certainly not between Andy and I. It was also to the benefit of the end product that Andy was personally involved in the mastering process.

So, in conclusion, not only is the Andy Roberts Anthology one of the most satisfying I’ve worked on in terms of getting a lot of wonderful music onto CD for the first time, it’s also been delightful to get to know Andy himself – a hugely under-rated artist and decent bloke, who’s been involved in a phenomenal amount of musical byways, bands and projects in his time, and indeed continues to be (check out the just-released 40th Anniversary Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band reunion concert DVD for an example). It was a particular pleasure to be able to bring Andy over to Belfast in December 2005 for an all-too rare solo performance, in a double bill with Irish trad legend Andy Irvine.

During the process of working on the solo anthology, Andy and I also began pursuing the legacy of his 1968-70 band Liverpool Scene – I managed to procur copies of four amazing programmes they made for Granada TV in 1968, while Andy (through a tortuous series of letters, phone calls, haranguing, brinkmanship and denouement when a ‘smoking gun‘ piece of letter-headed paper from 1970 was finally found) managed to effectively reclaim, from SonyBMG no less, the rights to the band’s four albums. Privately recorded live material from the period was also procured from folk club organiser Geoff Harden and erstwhile TV celebrity Doc Cox.

At the time of writing (April 2006) it looks very likely that a 2CD Liverpool Scene Anthology will appear via Sanctuary in 2007 – the 40th anniversary of the band’s founding. It also looks likely that a full release for Andy’s 1973 solo masterpiece Andy Roberts & The Great Stampede – probably with bonus BBC and/or demo recordings from the period – will appear later in 2006 via Market Square Records, while an expanded version of the 1976 LP Sleepers by yet another of Andy’s bands, Grimms, will appear on Hux. Andy’s also currently working on material for a new Plainsong album with Iain Matthews. The more Andy Roberts on CD the better, I say!

Coliin Harper, April 2006

Andy Roberts Anthology Sleevenote

‘I’m realising that my biggest problem, now as then,’ says Andy Roberts, ‘is that I get so bored in the studio. I just want to bang it down and get on with something else. In the ‘70s I was so busy rushing around from one gig to another, one session to another, one collaboration to another, that I couldn’t be bothered to polish anything in the way that other artists did. There wasn’t enough time. My favourite expression in the studio was “Will it affect sales?” If the answer was “No!” then it was good enough for me. It’s a failing.’

Andy’s ’failing’, though, has been responsible for an extraordinarily rich and, up till now, largely untapped (on CD) seam of music from the glory days of rock – intriguingly crafted, beautifully played, often luxuriantly produced (at odds with that ‘bang-it-down’ remembrance), and, taken as a body of work, the product of a man who deserves to be written back into the history which so curiously seems to have airbrushed him out or, at best, demoted his name to that of a Zelig-like footnote in the sories of other people.

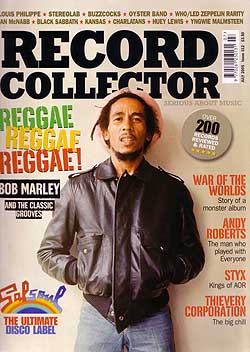

Andy Roberts is an enigma: a man whose story involves playing on hit singles while studying for (and achieving) a law degree in the ’60s; playing on an album produced by Jimi Hendrix; hanging out at Paul McCartney’s place during the Beatles’ studio years; playing the Albert Hall and touring America with Led Zeppelin in 1969; playing both 1969 and 1970 Isle of Wight Festivals; and, a decade later, finding himself a member of Pink Floyd for a couple of weeks. He might also claim celebrity as the Pete Best of The Rutles. And yet who but a handful of connoisseurs and train-spotters on the mighty railway of rock have even heard of the fellow? Andy Roberts didn’t disappear from the limelight – he simply moved sideways, out of its glare. Simultaneously (in a combination that is rare) both an artist and a journeyman musician, he decided to stop making records with his name on the cover after the dismal luck which all-but buried the 1973 album he regards as his best, Andy Roberts & The Great Stampede. He has remained a comfortably successful working musician ever since.

The insanely productive period which this compilation seeks to make sense of spans 1969 – 1973, and takes in mind-boggling, overlapping folds of commitment: that of being a solo recording artist (with four albums – one reappearing in three different guises); an in-demand session guitarist; a member of at least three bona-fide bands (Liverpool Scene, Everyone and Plainsong); and a serial stage and studio collaborator with the incestuous pool of musicians, poets and performance artists whose family tree includes the Scaffold, the Bonzo Dog Band and GRIMMS. Yet during the early years of the 1970s Andy Roberts’ default setting – for his professed ambiguity with the prospect in press interviews at the time – appeared to be that of a solo artiste. But let’s go back to the beginning…

Born in Hatchend, London, in 1947, Andy’s dad was a devotee of Music Hall comedy and his mum an afficionado of classical music. Both involved Andy in their enthusiasms from a young age and consequently, from formative exposure to slapstick and symphony concerts, Andy took up the violin at nine (taking lessons for nine years) and simultaneously dived into the skiffle boom that was sweeping Britain in the late ‘50s – owning his first guitar circa 1959.

‘I got a music scholarship to a public school in Essex,’ he explained, in an extensive interview with Ptolomaic Terrascope in 1992. ‘When I went there there was already a band called Flash Sid Fanshawe & The Icebergs. This was in 1959. They’d got guitars which they’d made in the school workshops and played very simple stuff which I thought sounded fantastic. By the time I left the school there was half a dozen quite good bands there. You could plug in and just make as much racket as you wanted.’

Andy’s school band, foreshadowing his long involvement with the wacky and the surreal, was known to its friends as Monarch T. Bisk & The Cherry Pinwheel Shortcakes – or, at least, would have been ‘but nobody could remember it all’. The band went through several stages – from a Shadows sound to Chicago R&B – ‘but I never thought of doing it for a living’.

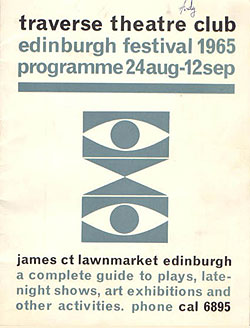

It was becoming embroiled in providing live music for a revue – written by a Shortcakes’ associate – at the 1965 Edinburgh Festival which led to the real beginnings of Andy’s path as a professional musician. The show ran for two weeks at the Traverse Theatre, and one of the acts following the play was Vivian Stanshall, who had recently formed the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, ‘doing mime, playing the tuba and generally camping around’. The theatre was also playing host to The Scaffold, a Liverpool comedy troupe comprising Roger McGough, John Gorman and Mike McGear (ne McCartney, Paul’s brother). Andy was really impressed with their show, and by a bunch of poets – including Adrian Henri – playing the venue during afternoons. Many strands of Andy’s career over the next decade and beyond would be interwoven with all of the above, all focused on this one venue in August 1965.

Andy returned to London and accepted an offer to study law at Liverpool University, almost immediately bumping into Roger McGough at a bookshop as soon as he got there. The ‘jazz and poetry’ movement was at its peak, and Roger invited Andy to dive in: ‘February 1966 was the first time I did a thing with him and Adrian Henri, at the Bluecoat Theatre in Liverpool. It just took off from there. Within a couple of months I was doing poetry events at The Cavern and playing with a band at the University. There was loads going on.’

Soon, on the back of a 1967 poetry anthology entitled The Liverpool Scene, Adrian Henri, Roger McGough and Andy, along with jazz saxophonist Mike Evans and songwriter/guitarist Mike Hart, were taking bookings as ‘The Liverpool Scene Poets’ Andy was also recording with McGough’s music/comedy outfit The Scaffold, on a series of singles which included their breakthrough hits ‘Thank U Very Much’ and ‘Lily The Pink’. Roger consequently had to drop out of the poetry gigs, leaving Andy to suggest to the charismatic Adrian Henri that all they needed was a bassist and drummer to become a bona fide band. Percy Jones and Bryan Dodson (later replaced by Pete Clarke) filled those roles respectively and The Liverpool Scene was born.

An album for CBS had already been recorded, prior to the band’s formation, called The Incredible New Liverpool Scene – basically Andy accompanying Adrian Henri and Roger McGough, recorded over a couple of hours in Denmark Street, London. BBC Radio’s champion of ’the underground’ John Peel took a shine to it and regularly booked the now fully-fledged band (or, as a duo, Roberts & Henri) for his show and for his own live engagements. He also nominally produced their first full-band album, Amazing Adventures Of… (RCA, 1968), in a recording deal secured by their new manager Sandy Roberton – a key figure in the careers of many now legendary acts at the progressive ends of folk and rock music of the time.

In 1968 Andy graduated in Law – having somehow found a way through a degree course in between singles with The Scaffold, concerts with the Scene and helping out on the Scaffold spin-off LP McGough & McGear, the other guitarist being Jimi Hendrix and the producer Paul McCartney. ‘I wasn’t professional at the time,’ says Andy, ‘but I was doing jobs that many professionals would have envied. I’d get calls to do a bit of recording in London, and I’d stay at Paul McCartney’s house – walk up and ring the doorbell and there’d be 85 girls hanging around outside. I didn’t even think twice about it. [But] 1968 was really when the working life started.’

The following year saw the Liverpool Scene at their peak – delivering their second album Bread On The Night, touring the UK on a three act bill with Led Zeppelin and Blodwyn Pig, playing to 150,000 at the Isle of Wight Festival (on the day of Bob Dylan’s much-heralded ‘comeback’ performance) and touring America for a gruelling, and revelatory three months. ‘Absolute disaster,’ is Andy’s verdict on the tour. ‘We suddenly came up against the utter reality of it. With a British audience, given this poetry and a band that were never rehearsed, we got away with it through being so different and [through] our verve and irreverence. None of which worked in America.’

The American experience would nevertheless inspire the band’s best work – the lengthy ‘Made In USA’ suite, one side of their last LP proper, St Adrian Co, Broadway And 3rd (1970) – and which would filter into Andy’s own work for the next few years. It also forced him to re-examine his own direction: ’[Before America] I was stupid enough to still think I could be Jimi Hendrix. I wanted to be a star. You do when you’re young – you don’t realise that everybody has their role, and that wasn’t mine.’ Andy still recalls some sage advice he received around this time from folk-baroque guitar hero Davy Graham : ’You only person you should be in competition with today is yourself yesterday’.

The first Andy Roberts album, Home Grown, was recorded in late 1969, and built upon the quirky solo tracks he had to date peppered among the jazz/poetry workouts on Liverpool Scene albums and radio sessions. ‘The Raven’, featured on 1968’s Bread On The Night and heard here in a superior unreleased version from 1969, was one such; ‘Home Grown’ itself was another. Those two tracks conveniently represent the poles of Andy’s writing: the profound and the purely comedic. Making these parameters sit well together on one piece of vinyl was the question which would quickly colour Andy’s own view of the album – or, at least, in its original form, as released by RCA (under a production deal with Sandy Roberton) in March 1970.

‘Infinitely listenable and beautifully arranged, with excellent guitar work from Andy. A lovely, peaceful album.’ That was Disc’s judgement on this mesmerising and atmospheric rough-hewn debut, on which Andy was backed on some tracks by the rhythm section from Mighty Baby (another of Sandy Roberton’s charges), with brass arrangements from future Jethro Tull man David Palmer.

An eclectic album, punctuated with brief bursts of violin and organ noodling, the key tracks included the ragtime/country flavoured comedic songs like ‘Home Grown’ and ‘Gig Song’, the impressionistically autobiographical ‘Moths And Lizards In Detroit’ (first of the ‘American’ songs) and ‘Queen Of The Moonlight World’ (inspired by a visit to London Zoo), and the altogether gothic ‘Applecross’, inspired by a weekend in a village of that name in north-west Scotland. The spooky vibe was continued on the traditional ‘John The Revelator’ and a funky cover of ‘Spider’ John Koerner’s ‘Creepy John’.

Andy performed several items from Home Grown on John Peel’s Top Gear radio show, plus the driving non-album track ‘You’re A Machine’, on which he was again backed by Mighty Baby. A previously unreleased rehearsal of the track, recorded shortly before the BBC session, is included here.

The Liverpool Scene finally split, onstage at a London gig, in May 1970. In Andy’s recollection (’Adrian attacking Mike Evans with a mike stand’) it had been building up for a while. Soon after, Andy crashed a motorcycle and was out of action for a couple of months, but recovered well enough by July to accompany Adrian – along with Dave Richards on bass, Alan Peters on trumpet and John Pearson on drums – to Norway for a couple of gigs booked as the Liverpool Scene. The trip would inspire Andy’s ‘Sitting On A Rock’.

Regrouping with Adrian had been Andy’s hope, but it wasn’t to be. Despite the Scene’s perceived success, as Andy explained to Record Mirror’, ‘nobody really made any more than about £20 a week. I was going to form a band with Adrian after the Scene split, but he backed out. You’ve got to remember, he’s 39 and £20 with the Scene wasn’t much.’

As Adrian went on towards becoming, in tandem with his poetry, a well-regarded visual artist and college lecturer, Andy pressed ahead with his new band – now titled Everyone. Retaining Richards and Pearson from the Norway trip, he added John Porter, on guitar, and took Porter’s recommendation to bring in Bob Sargent on keyboards which, he now says, ‘was probably the worst of several moves’.

Nevertheless, the picture that emerged from the band’s debut music press feature, in Disc, September 19, 1970, was one of a bunch of happy campers, ready to take on the world. Having played one gig – the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival, no less – and on the cusp of their debut album, Andy declared, ‘We’ve reached the stage now where we’re over-rehearsed and under-performed.’ In retrospect, he prefers to sum up the period with a rejoinder worthy of Spinal Tap: ’Rented a house near Stonehenge; took lots of drugs; didn’t rehearse enough.’

The resulting album, Everyone, released in January 1971, while well-recorded was, in Andy’s view, ‘frankly, a bit of a mess – there was Bob’s stuff and my stuff and it didn’t really meet in the middle.’ The album included four songs fronted by Andy: another Koerner cover, ‘Midnight Shift’, and a beautiful trio of originals in ‘Don’t Get Me Wrong’ (a reflection on recent US student uprisings against the Vietnam war), ‘Sitting On A Rock’ and ‘Radio Lady’, the latter being another memoir of the Scene’s US tour. All three originals are included here, with ‘Radio Lady’ appearing in the form of a superior mix first released in October 1971 on an US Roberts compilation, on the Ampex label, confusingly called Home Grown (more of which below).

Whether Everyone could have found the common musical ground to continue is academic, for the band were effectively destroyed by a tragic accident involving their two road crew and a friend on the A33 in November 1970. The group’s van and gear were written off and Paul Scard, Andy‘s loyal roadie, lost his life. Andy saw out some contractual obligation gigs as a three-piece with Richards and Pearson but ‘come December 1970 that was it. I didn’t want to do anything.’ By the time the group’s first (and last) album appeared, on B&C, there was no wind in its sails.

Shortly after the crash, Andy and Dave Richards had rented a house for a month on the outskirts of Northampton. This brief period would yield the material that found its way onto Andy’s next solo album proper, Nina And The Dream Tree, a year later. As Andy explains, ‘We played a lot of Bezique, and played Neil Young and Grateful Dead records. I was visited by Polly James [actress in the popular TV sitcom The Liver Birds], with whom I was seriously involved, and who is the subject of the whole of the first side of Nina . Polly and I spent New Year’s eve at Tommy Steele’s house.’

Andy was back in London by January ‘71, living with his folks and wondering what to do, when he got a call out from Paul Samwell-Smith, ex-Yardbirds bassist and now a record producer. He was looking for a guitarist to work on a debut solo album by former Fairport Convention and Matthews’ Southern Comfort vocalist Iain Matthews – hot property after MSC’s September 1970 No.1 hit single with ‘Woodstock’. Andy and Iain hit it off together, and the new association with himself and Samwell-Smith ‘put me into seven months’ intense studio work Iain and Cat Stevens and so on. Then Sandy Roberton was saying I hadn’t done a solo album for a year and should do something…’

Work on the Iain Matthews album (If You Saw Thro’ My Eyes) spanned January to March 1971 (April to May ‘71 would see further studio work with Iain, which became his next album, Tigers Will Survive); during March he also worked on the Mike McGear LP Woman; and he was also, as a Melody Maker feature of March 27 put it, ‘experimenting on a solo album, using vocal backing from three West Indians (“but no flash guitar”)’. Those backing singers, who played a crucial part in the magical sound of Nina And The Dream Tree (recorded sporadically during the next few months and released on Pegasus in October 1971), were Mike London and Mac and Kathy Kissoon. Three pieces of Nina’s jigsaw had been debuted on a BBC session for Bob Harris earlier that month – ‘Keep My Children Warm, ‘I’ve Seen The Movie’ and ‘Welcome Home’ – although the listing of musicians involved, essentially a reunion of Everyone, as given in Ken Garner’s In Session Tonight (BBC Books, 1993) strikes Andy in retrospect as ’hugely unlikely’.

Much of the Melody Maker interview, by Michael Watts, dwelt on Andy’s enthused speculations on ’a new multi-media venture entitled GRIMMS’, a surname-acronymic sextet involving himself, the three members of The Scaffold plus Viv Stanshall and Neil Innes from the Bonzo Dog Band, with aspirations to being a comedic, theatrical, surreal revue ensemble with musical content influenced by German satirical cabaret and kitsch Las Vegas crooning.

The periodic appearance of references to GRIMMS or aggregations of its constituent parts in the music press of the early ‘70s is a bit like the Cheshire Cat to anyone hoping for simple linear development in the biography of Andy Roberts. The GRIMMS story, of course, goes back to that 1965 Edinburgh Festival melting pot, but as an active unit (whose membership would be fluid enough to make its very acronymic name a kind of surreal statement in itself), its time had not yet come. In spite of all the talk of its imminence in the March ‘71 Melody Maker piece, Andy can recall no GRIMMS activity until literally two shows later in the year, at Greenwich and Corby, the former featuring The Who’s Keith Moon on drums. ‘Both of these were booked as Scaffold gigs,’ says Andy, ‘and I don’t think the punters were all that pleased!’ GRIMMS became a regular performing entity in 1972, when Andy was otherwise engaged as a member of Plainsong. But in being, by the time Plainsong folded in December ‘72, an established entity with a decent UK tour coming up it provided Andy’s momentarily off-the-rails career with a soft landing. The group, with fluid membership, enjoyed continued live popularity during the mid ‘70s and recorded three albums (GRIMMS, 1973; Rockin’ Duck, 1973; Sleepers, 1976). Andy‘s ‘Bluebird Morning’, from Sleepers (reissued by Hux, 2005), is included here as a whimsical memoir to his early ‘70s solo career. Speaking of which…

As Andy explained to Michael Watts, after the Everyone experience ‘the idea of forming a [purely musical] band is out, and so is the idea of joining one… If I had nothing to do I’d put a rucksack on my back and do the folk clubs. It’s a living. But it’s not what I want to do, ideally. In fact, I don’t know what to do definitely… [But] I’m enjoying the new-found freedom of not being tied to a rock band, both mentally and artistically.’

During the early summer of ‘71 Andy was certainly enjoying himself playing shows with a proto-GRIMMS outfit billed as the Bonzo Dog Freaks. If this was a blast of the future, Sandy Roberton had engineered a blast from the past: a new lease of life for Home Grown.

Somewhere between 1970-71 Sandy’s licensing allegiance switched from RCA to B&C/Pegasus. Consequently, in June 1971, Andy found himself promoting it all over again:

‘We’ve remixed and re-recorded some of it,’ Andy explained to Sounds, ‘and changed some of the tracks which didn’t quite work the first time. So this is almost a different album. It’s certainly better than the original one and bears more relation to me as I am now – but it’s still 18 months old. To confuse the issue still further, there’s an album going to be released in the States which will also be called Home Grown because apparently they like the title, but that one will only have three tracks from the original album, and four or five totally new ones which haven’t been released here yet. This means that America will be half an album ahead of here, [but] I’m reluctant to let those tracks go unreleased over here…’

(Most of the Home Grown tracks on this compilation come from the B&C mixes – their CD debut – save for ‘Moths And Lizards In Detroit’ which, though significantly revamped for B&C, loses something of the careworn atmosphere of the original. The B&C album included one entirely new track, ‘Lonely In The Crowd’, also included here.)

Home Grown’s re-release provided an excuse for Andy to perform, supporting Procul Harum, at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall, backed by Dave Richards and Mighty Baby’s Ian Whiteman and Roger Powell. It would be the stage debut of the Nina material, and led directly to Andy getting the support slot on a Steeleye Span UK tour later that year.

During July ‘71 Andy was able to tell Melody Maker’s Karl Dallas that: ‘For the first time I’ve got a coherent direction. Now I have personal statements I wish to make, though I don’t want to knock them in with a sledgehammer.’ Dallas was given a preview of the new recordings and was rightly impressed: ‘There is a great deal of warmth in his work,’ he wrote, ‘a fellowship for his kin which brims over… His singing voice has matured incredibly and his use of the electric guitar is haunting, reminiscent sometimes of Richard Thompson on top form…’

Andy was often telling the press that it was only during the McGear and Matthews sessions earlier in the year that he found his voice on the instrument, and the quality of his electric playing – a master of texture and atmosphere – was one of Nina’s revelations. Then again, spending August-September ‘71 on an Iain Matthews tour of the States as a trio with Richard Thompson himself can’t have done any harm.

As before, Andy’s US tour experiences would be a rich seam for his song writing. Time spent with one Karen Goskowski at the Poison Apple in Boston would yield three songs, first heard on his country flavoured Urban Cowboy LP in 1973: ‘Poison Apple Lady’, ‘Urban Cowboy’ and ‘New Karenski’. The first of these is heard here in a demo version recorded in November 1971. Some of the credit for Andy’s new skills at honing personal experiences into his creative process was down to Iain Matthews: ‘Iain has brought me more out of myself,’ he explained to Record Mirror in August, ‘he’s been a great influence. I’ve had to cultivate my lack of self-consciousness to the point where I’m ludicrously casual about the whole thing. A nice way to work…’

Right after the tour Andy recorded his contribution to Richard Thompson’s solo debut, Henry The Human Fly, and in October Nina And The Dream Tree, long in gestation, was finally released. Andy toured the UK in support of the record, as a trio with Bobby Ronga and Dave Richards, as guest of Steeleye Span. ‘A great pleasure,’ Andy recalls. ‘All the gigs were great.’

Typically, Andy was already working up a whole new batch of songs – including ‘Poison Apple Lady’, ‘Richmond’ and ‘Elaine’ which he aired on a Bob Harris BBC session in November. That same month he also performed live with Viv Stanshall and others as the Human Beans (yet another mercurial Bonzo-related project) and was working on the Bonzos’ reunion album, Let’s Make Up And Be Friendly, at the Manor Studio – ‘where Mike Oldfield was recording Tubular Bells in our down time!’

A late November interview with Mark Plummer for Melody Maker touched on many of the pies Andy had fingers in. Plummer’s conclusion was interesting: ‘From talking with Andy I got the impression that although he genuinely wants to entertain and loves working with as many people as he can cram into his diary, a lot of it is down to a fear about going onstage as a front man.’

Right on cue, Andy agreed to submerge himself in a band with Iain Matthews, Bob Ronga and Dave Richards – to be known as Plainsong. The group, a country-influenced vocal harmony outfit, spanned the entirety of 1972, recording the classic In Search Of Amelia Earhart and the (at the time unreleased) Plainsong II, and toured Europe extensively. Save for backing Adrian Henri on a couple of BBC radio dates, Andy’s focus for the whole year would be the band. And then, around Christmas ‘72, with Matthews lured to a solo deal with Elektra, it dissolved in rancorous disappointment.

By way of some consolation, Andy secured a solo deal himself with Elektra – yielding two albums in 1973, Urban Cowboy and Andy Roberts & The Great Stampede, the final solo albums he would make. Immediately after the Plainsong split, though, Andy was able to jump on board an already-booked GRIMMS UK tour (that band having built up a live following the previous year, without Andy’s involvement). In Andy’s words ‘the best antidote to the Plainsong blues. A fantastic relief.’

Urban Cowboy, featuring the likes of Richard Thompson, Neil Innes, Iain Matthews and Martin Carthy, and consisting of some newly recorded material and some tracks, like the fabulous ’Richmond’ (covered by Shelagh McDonald on The Shelagh McDonald Album in 1970 – half of which was produced by Andy, uncredited), which were in the can prior to the Plainsong experience, was released with lightning speed in March 1973. This CD represents all but one of that album’s tracks in either LP or demo form, bar one: ‘All Around My Grandmother’s Floor’, a fabulous Plainsong left-over which can be heard on the forthcoming Plainsong ‘complete works‘ 2CD set on Water Records.

After the GRIMMS dates Andy put in time working solo in folk clubs, and got married (to Jacqui Byford) in May – honeymooning in Jamaica for a month. Andy had been intrigued with reggae since working with Mike London and the Kissoons on Nina, and wrote a number of songs with reggae influence coming out of the Jamaica experience – ‘Living In The Hills Of Zion’, heard here in demo form, recorded right after the honeymoon in June ’73, being the best.

The following month Charisma released the compilation Andy Roberts, featuring material from the pre-Plainsong albums, but Andy was already focused on creating what he regards as his finest album, Andy Roberts & The Great Stampede – clearing his diary for a whole month in the summer to record it, with musicians including BJ Cole (pedal steel), Patto’s Ollie Halsall (lead guitar), ELO’s Mick Kaminski (violin), Zoot Money (keyboards) and Sandy Denny associates Pat Donaldson (bass) and Gerry Conway (drums). The result was a powerful, luxuriantly produced soft-rock album which moved him once and for all away from any assumptions of being part of the British folk scene – a scene to which Andy was never closer than semi-detachment.

‘The reason I called it Andy Roberts & The Great Stampede was that I was hoping people would think of it as a band. I don’t want people to think that the only thing that’s on it is me,‘ Andy explained in a Melody Maker interview of December 1973. ‘It’s the first time I’ve ever made an album in one go… It’s the first one that I’ve done all the vocals on – all the harmonies. That was something that I got out of Plainsong.’

Andy had just finished a second sizeable UK tour with GRIMMS when he gave the interview. ‘It’s been about equal amounts of solo and GRIMMS with a bit of nothing in between,’ he said. ‘It’s been a good year artistically in that I’ve done something completely different to what I was doing last year, and I think that I achieved something last year. So if I’ve achieved something else this year that’s alright… I’m very pleased with [The Great Stampede]. The next one will be better.’

Unfortunately, there would be no ‘next one’. Andy had been able to promote both of his 1973 albums with BBC radio sessions and press interviews, but unfortunately – just as he felt he’d delivered his best work with The Great Stampede, his luck was running out. The three-day week, vinyl shortages and the sale of Elektra to David Geffen (with implications for their UK pressing and distribution) effectively wrecked the album’s release. While Andy had been hoping to put together a band to support the album, there would be no tour. He believes only around 1500 copies managed to trickle out and, tellingly, has not once in over 30 years been offered a copy to sign.

‘The thing never got a proper a release,’ he reflects, ’there wasn’t enough copies, they weren’t available on the declared day and the review copies didn’t go out. It was heartbreaking.’ A future CD release of Andy Roberts & The Great Stampede in full is planned, so for this compilation we’ve chosen merely a taster in the beautiful ‘Home In The Sun’.

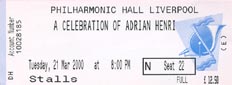

Disillusioned with his solo career, Andy Roberts – one of the great neglected singer-songwriters of the era – bowed out with a final BBC session for his old pal John Peel in March 1974. The following month he dived into a Liverpool Scene reunion tour, with Adrian Henri, Mike Hart, Dave Richards on bass and Mike Kellie on drums. Sadly unrecorded, it was, to Andy‘s recollection, ‘musically the best line-up of all time. And I was a simpler, straighter, less pretentious kind of guy, I like to think! This late-flowering version of a poetry band rocked hard and worked a treat.’

From then on Andy became simply a musician for hire, working in theatre and seeing out the decade with GRIMMS and as a member of both Roy Harper’s band and the Albion Band. In 1980 he began a four-year tenure with comedy country icon Hank Wangford’s band, taking time out in 1981 to join an expanded version of Pink Floyd to perform The Wall in Germany and at London’s Earl’s Court. Theatre, TV and film soundtrack work rolled on thereafter, interspersed with occasional gigs backing Adrian Henri’s poetry. In 1990 a chance meeting with Iain Matthews at a pub in Brighton (where Andy now resides) resulted in a Plainsong revival, which has thus far delivered several new albums and periodic tours.

With much of the Liverpool Scene, GRIMMS and solo recordings now reverting back to himself and the members bands concerned, future possibilities include a Liverpool Scene box set, an expanded version of GRIMMS’ Sleepers and a full release for the long-lost Andy Roberts & The Great Stampede – all from the original masters. For updates on these projects, and for loads more on Andy’s incredible, labyrinthine career, keep checking out www.andyrobertsmusic.com

Because he’s worth it.

Colin Harper, April 2005